Entry #8: Jeffrey Dahmer—Psychopomp Extraordinaire

With his longed-for 'shrine' Jeffrey Dahmer hoped to breach the border that demarcates life from death. And in so doing find 'peace' and 'power.'

“Psychology…far from debunking religiosity, confirms man as an essentially spiritual being. The aspect of Jeffrey Dahmer which lay untouched by his trial was his embryonic mysticism.” —Brian Masters, The Shrine of Jeffrey Dahmer

IT’S A TOUGH CALL. Was it his cannibalism or his thwarted wish to build a magical power center—a shrine comprised of the skulls and bones of his victims—that makes Jeffrey Dahmer’s saga so incredibly bizarre?

Should you be inclined to plow through the volumes of Dahmer’s transcribed confessions and psychological profiles, as I have done while researching my book, your mind eventually ‘adjusts’ to the testimonies of his cannibalism.

Why?

The ultimate taboo remains a perennial feature of modern media’s obsession with zombies, vampires, and werewolves. The steady inculcation of gore has made us superficially immune to the implications by presenting corporeal ghoulishness as entertainment.

Not that this is an easy topic to consider, in its literal sense, as it applied to Dahmer. But cannibalism is an act as old as humankind. Historical references to the offense fill studies of ancient religions, primitive tribal rites, fairy tales, and myths.

Even today, the Catholic church practices what it calls transubstantiation, where the devoted are assured that the small wafer and wine they ingest during communion is literally the ‘flesh and blood’ of Jesus. As a child, this delusion freaked the shit out of me. But still, as a good Catholic boy, I was forced to imbibe. Little wonder I fled the church as soon as I was able.

For Dahmer, who existed hermetically sealed in a world of feral fantasy and moral degradation, there was little difference. As he explained to several psychiatrists during his various evaluations, by ingesting the flesh of his victims, he was simply ‘making them a part of me.’

Here’s the thing—was this true?

Did he actually commit cannibalism?

Dahmer was a cagey but indiscriminate liar. His capacity (or was it simply his unbelievable luck?) to evade capture year after year, close call after close call, is an instinct we associate with the reptilian.

True, he displayed a razor-sharp memory when confessing to each of his seventeen murders, one going back almost 15 years. But beyond his stated intention to bring resolution to the families of the victims, he also considered this detailing of names and dates as the one good thing he could accomplish in his life—after he was captured. But before this, he harbored a more insanely ritualistic vision.

Dahmer displayed a restrained, affectless manner of retelling the gruesome particulars of his murders. This disparity conjured a waylaying sense of confusion and disbelief in the listener. It’s akin to a hypnotist working his best gimmicks on an audience.

Unlike others who have watched his two interviews that were broadcast on national television in the early 90s, I discerned another hybrid of Dahmer’s madness pulsing beneath his monotone confessions.

Network reporters Stone Phillips and Nancy Glass did their best to maneuver the grotesque details. Although Glass, sitting across from Jeff, eventually morphed into a literal version of the descriptor: “A deer caught in the headlights.”

The most gonzo of moments occurred at the close of the Stone Phillips interview when Dahmer’s attention landed on a small carrying case that was propped on a nearby chair. He then disclosed, while exiting the makeshift studio, that the box-like case was similar to the one he used to store the head of one of his victims. A trophy that he kept in his locker at the chocolate factory that employed him. He shared this fact in the nerd-like way that someone on the spectrum employs to make an impression on others.

You could feel the crew in the room recoil as his father moved in to interrupt him. But for Dahmer, this was simply another intriguing tidbit among his long list of ‘achievements.’ After registering shock, I experienced a degree of sadness that took me all evening to shed. And I flashed back to the summation that detective Pat Kennedy made shortly after Dahmer’s arrest: “Trying to comprehend Jeffrey Dahmer is to understand or attempt to understand the power of loneliness and alienation at its absolute core.”

So let’s call Dahmer’s mode of confessing and sharing: the thrill of recapitulation.

True, he might have attempted to free himself from his memories by ‘telling all.’ A projection/injection designed as a hand-off. A sort of, “Here, free me from this horror. I’ve told it; now it’s yours to carry with you.” But consider your mind’s inability to consciously dislodge from recalling content you wish you’d never seen, heard, or read. It’s impossible.

But if you watch the interviews closely, the way Dahmer’s eyes grip the eyes of the listener—there’s another influence at work. Perhaps the aftereffects of his brutality were given a second life by shrinking the heart of the interviewer. Mentions of cannibalism could only up the thrill factor exponentially.

Biographer Brian Masters, who facilitated a year-long Hannibal Lecter-like interview with UK serial killer Dennis Nilsen—in hopes of deriving a kind of psycho-to-psycho close read on Dahmer—wrote in Vanity Fair:

It is Nilsen’s opinion that claims of Dahmer’s cannibalism are probably not true. “He is talking subconsciously,” Nilsen told me in our recent interview. “It's a kind of wishful thinking. What he really wants is spiritual ingestion, to take the essence of the person into himself and thereby feel bigger. It's almost a paternal thing, in an odd way.” [Italics are mine.]

Masters then adds a coda: “Milwaukee Police Chief Philip Arreola told The Milwaukee Journal early in the investigation that ‘the evidence is not consistent’ with cannibalism, implying that none of the body parts which littered the apartment supported Dahmer's contention.”

Later forensic reports claim that there may have, indeed, been particles of human flesh on Dahmer’s eating utensils. But the only person who knows the truth is dead.

Let’s move on to Jeffrey’s power center or shrine.

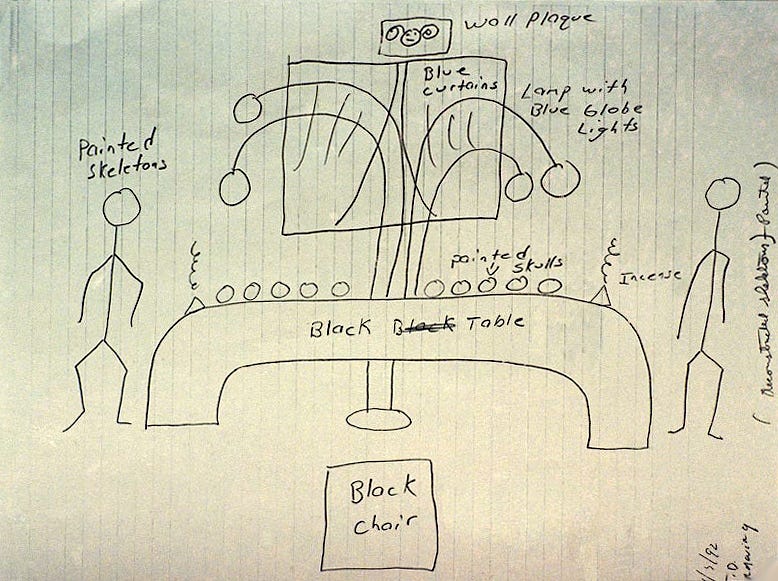

Here is the diagram that Dahmer drew for one of his attorneys, Wendy Patrickus. Pay attention to the emphasis on what Masters defines as the shrine’s “mystical absolutes of symmetry.”

Now I want to engage my astrological knowledge of Dahmer’s birth chart to highlight the worldly achievement that Dahmer might have attained should he have directed his inherent promise into constructive channels.

Dahmer’s horoscope held the potential for renown in several different vocations, primarily artistic or scientific. As with most Gemini natives, he might have been successful in both. Instead, he had the remains of eleven preserved bodies to forge into his ideal of achievement—the construction of his longed-for shrine or altar. Of the shrine, he told several different shrinks after his arrest: “Six months later, and I would have had the whole thing constructed.”

And still, acclaim and ‘greatness’ would arrive through infamy. Dahmer is often mentioned in the same breath as Hitler and Stalin when polls are taken of the most despicable humans to have landed on planet Earth.

Dahmer’s Libra ascendant required enriching relationships to impart a sense of fulfillment and creative expression. The ascendant works this way in the horoscope. The sign’s attributes are nascent drives we integrate deliberately. The ascendant’s qualities are not ‘givens.’ We express them through practice and perseverance. The more we succeed, the more individualistic we feel. Thus, there is a constant tension to express the ascendant’s qualities, and when we do, our originality has found purchase. Similar to the sign Gemini (Dahmer’s Sun and Mercury placements), Libra is a connector, a bridging instinct that unites and synthesizes different worlds. Libra is also inherently aligned with the concept of symmetry, as Masters alluded to above.

For Dahmer, his ascendant’s push to develop sensuous relationships (Venus, the sign’s ‘ruler’ in Taurus) was at odds with his horoscope’s Moon and Mars in Aries—a self-referential, one-pointed drive to have one’s way regardless of how egoism impacts others. If Libra promotes ‘the need for others,’ Aries is focused on ‘the needs of the self.’ But Dahmer’s Arian markers were placed in opposition to his ascendant. Where the ascendant symbolizes ‘me,’ the descendant—the opposing seventh house— is a stand-in for ‘you.’ With the maternal Moon melded to warrior-like Mars, placed in the area of the chart aligned with bonding, the infant experiences the mother (our original ‘other’) as a self-driven competitor, a potential destroyer. A gorgon who can turn men to stone with her stare.

I believe this explains Dahmer’s singular rigid posture: spine ramrod straight, shoulders squared, arms stiff at his sides. And his mechanical, on-spectrum robot state. A shuffling gait that first appeared somatically around the age of seven (according to his father) when Saturn touched off Dahmer’s Aries placements. The transit literalized (Saturn) the danger Dahmer experienced from his mother. Where the best offense is a defense, Dahmer turned himself to stone as protection against what should have been his source of nurturance and protection.

In The Divided Self, psychiatrist R.D. Laing details three forms of anxiety encountered by the ontologically insecure person (someone whose being-ness does not feel safe within his or her holding environment). The first, ‘engulfment,’ involves the loss of oneself by feeling enclosed, swallowed up, drowned, eaten up, or smothered by another person. The second, ‘implosion,’ relates to the child’s environment feeling volatile, explosive, and annihilative. And then, finally, ‘petrification and depersonalization.’ This latter defense became Dahmer’s baseline orientation. However, all three anxieties moved one into the other throughout his developmental years.

Laing defines petrification as,

“A particular form of terror, where one is petrified, i.e., turned to stone. The dread of this happening…the possibility of turning, or being turned, from a live person into a dead thing, into a stone, into a robot, an automaton, without personal autonomy of action, an it without subjectivity.”

Petrification’s adjunct is depersonalization, which, as Dahmer told the arresting officers and shrinks who interviewed him, was the overriding psychological state that allowed him to murder with such alacrity and indifference. But depersonalization is a circular defense. Depersonalized and turned to stone himself, it was easy for Dahmer to do the same to others. One ‘thing’ kills another ‘thing.’

Consider this. Dahmer was under assault from his mother from the moment he was conceived. As Dahmer’s father wrote in his book A Father’s Story, Joyce Dahmer was taking over 20 different medications and tranquilizers, including morphine, regularly while pregnant. In a literal sense, the fetus was stewing in the chemical brew from the placenta. This explains his effortless slide into alcoholism at the age of thirteen (according to his younger brother). Bringing alcohol to school regularly, Dahmer told one student—who bothered to ask about the paper cup filled with scotch on his desk—“It’s my medicine.”

As a teenager, Dahmer had freed himself from the quotidian world we consensually call ‘reality’ and was developing his impressionable teenage mind in the altered, uninhibited state that alcohol delivers. Already he was traversing the borderland between this world and ‘another.’ Drinking himself frequently, into stupors or blackouts (the latter was a condition that allowed him to unknowingly murder his second victim.)

When I read Joyce Dahmer’s section in the book The Silent Victims (a collection of essays by women who suffered the ignominy of having birthed criminals), I was stunned by his mother’s relentless, all-encompassing narcissism. Her son, the ‘star’ of the story, was mentioned sporadically, almost as an afterthought. Instead, she offered unrelated details about her childhood, her accomplishments, her disappointments, her apartment and garden, and her air conditioner, which grew louder and louder and louder during the phone call that alerted her of her son’s atrocities.

Very little was revealed, in a self-aware way, about her maternal relationship with her son unless it was referencing Joyce’s discomfort about Jeff’s strange, sullen, and withdrawn ways. “He never shared anything with me.” Oh, brother. What child would dare?

The telling moment, another stunner that knocked me on my ass, was when Joyce detailed how, after having not seen her son in six years, she traveled from California to visit him in prison. There, during their reunion, Dahmer forced her to listen to the grotesque details related to each of his seventeen murders. How he committed them, how he dismembered and decapitated the bodies, and then disposed of (or preserved) the ‘remains.’ He offered that this confession was necessary for transparency between mother and son. In contrast, I read this as violently aggressive payback to the woman—a key component to his necrophilic psychological state—that abandoned him as a riddle—a shy, quiet boy that couldn’t embrace Joyce’s hypomanic, self-absorbed mode of mothering.

Am I ‘blaming’ Joyce Dahmer for Jeffrey Dahmer? No. But the child-mother bond is the central relationship in each of our lives. And for Dahmer, with his fierce need to be responded to through touch and the sensual realm, a mother like Joyce was anathema. While still an infant, Jeffrey was not allowed to be touched by anyone lest an infection be passed to the baby. Joyce didn’t like breastfeeding, so that was out. She also couldn’t tolerate disruptive noises of any kind, and most babies are generally anything but quiet. Infant Dahmer became a doll-like thing for her to dress up and display while acting out her notions of motherhood.

Dahmer was lodged in a perpetual paradox. He longed for close bonding with others but was petrified of their vitality, aliveness, and separate sense of identity. Forces that might engulf him, explode him, or turn him to stone. How to meet the natural need to connect and merge with others? Render the threatening object inert and then, quietly, without interruptions, fuse. And this became one of Dahmer’s earliest sexual obsessions.

For a child approaching puberty, the swirl of Dahmer’s contradictory needs and defenses found purchase in his imagination—where fantasy, for each of us at this developmental phase, fell into what the neo-Freudian psychologist Erich Fromm describes as a necrophilous orientation. Before committing his first murder—two weeks after graduating high school—Dahmer had already fantasized about clubbing a jogger in his neighborhood over the head and then dragging the man’s inert body into the forest to lay down with and experiment with sexually.

Fromm classified two aspects of life. The first he called the biophilous. He posits this path as “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive; it is the wish to further growth, whether in a person, a plant, an idea, or a social group.”

The second he called necrophilous. This ‘direction’ in life encourages fright, routine, mechanical order, control, and exploitation of others. He isn’t claiming the necrophilic aspect leads to literal necrophilia (although, of course, with Dahmer, it did). But Fromm details what develops in people when they disconnect from the biophilic—the living of life in support of life instead of death and destruction.

In his book The Pathology of Normalcy, he notes:

The capacity for the attraction to death is one which is given in any human being if he fails in development of what I would call his primary potentiality, namely to be related to life as something which is interesting, something which is joyful, or to develop his powers of love and reason.

If all of these things remain incomplete, then man is prone to develop another form of relatedness, that of destroying life. By doing this he also transcends life, because it is as much of a transcendence to destroy life as it is to create it.

Much of modern culture is necrophilic. Our proliferation of nuclear weapons presents an entirely necrophilous orientation, as does the onslaught of public shootings that occur regularly. With the Dooms Day Clock poised on the lip of midnight, we’re closer than ever to triggering an irrevocable thrust into extinction. It’s fitting that Dahmer remains a perennial fascination, especially now as he’s reasserted himself into our imagination through mainstream and social media. People remain mesmerized by the symbolic juncture Dahmer occupied between life and death.

Loneliness, alcoholism, and eventually madness allowed Dahmer to move effortlessly between what are seemingly distinct realms—despite the fact that death is always entwined intimately around what is alive and thriving. As the writer Janet Malcolm put it: “In some secret way, Thanatos nourishes Eros as well as opposes it.”

As a journeyman between worlds, Dahmer forged his most satisfying relationships within the silent realm of the dead. As Masters noted in his book Shrine, the only people who truly knew Dahmer were those that he put to sleep and destroyed. By delivering them into the underworld, Dahmer became a psychopomp extraordinaire.

Dahmer hoped to build his shrine as a monument to his originality and achievement. Sitting in his tiny apartment amidst the spooky glow of the blue lights hovering above his power center, he hoped to ‘meditate’ and receive transmissions from the ‘other’ world, a world that, from his childhood forward, he’d associated with the nourishment and security that alluded him.

Finally, he would have this vital but unpredictable world under ‘complete control.’ As he repeated often, Dahmer had gone his entire life without ever feeling in command in a worldly sense. Paradoxically, what he did control and administer is the greatest power one individual holds over another, the ability to steal away another’s life.

When asked by those who interviewed him what he hoped to achieve with his shrine, his answer was as ordinary as anything you or I might wish for—peace, power, money, and success. But as he once told one of the shrinks who interviewed him—in a moment of bald-eyed clarity—“I should have got a college degree, gone into real estate and bought an aquarium.”

Until next time,

Thankyou so much for this. Your knowledge on so many levels, is incredible. You go deep into the physcology of the mother/baby bond, which I find absolutely fascinating. I am currently reading "The Denial of Death " and "Escape from Evil" by Ernest Becker, which is along the same lines. This was so interesting, I can't wait to read more of your work.

When these emails arrive I have to go through a back and forth in my head. I mean I'm not sure I want to read them, as compelling as your writing is, it's still 'Jeffrey Dahmer'. But you make them worth the time I spend Fred. This one doubly so. I do love how you stay true to your astrological roots, and also these new interweaving of psychological insights are fascinating. I think I want to read more of Fromm's material (he is new to me). Can you recommend a good intro type of book on him?