“In some secret way, Thanatos nourishes Eros as well as opposes it.” —Janet Malcolm

This is part 2 of my interview with the artist Volk Kinetshniy.

Part 1 of our discussion is published here.

While researching my novel, I wept several times when I encountered graphic details of how Dahmer murdered the seventeen boys and men that crossed his path over the years. How do Dahmer’s victims fit within the equation of your artistic inquiry?

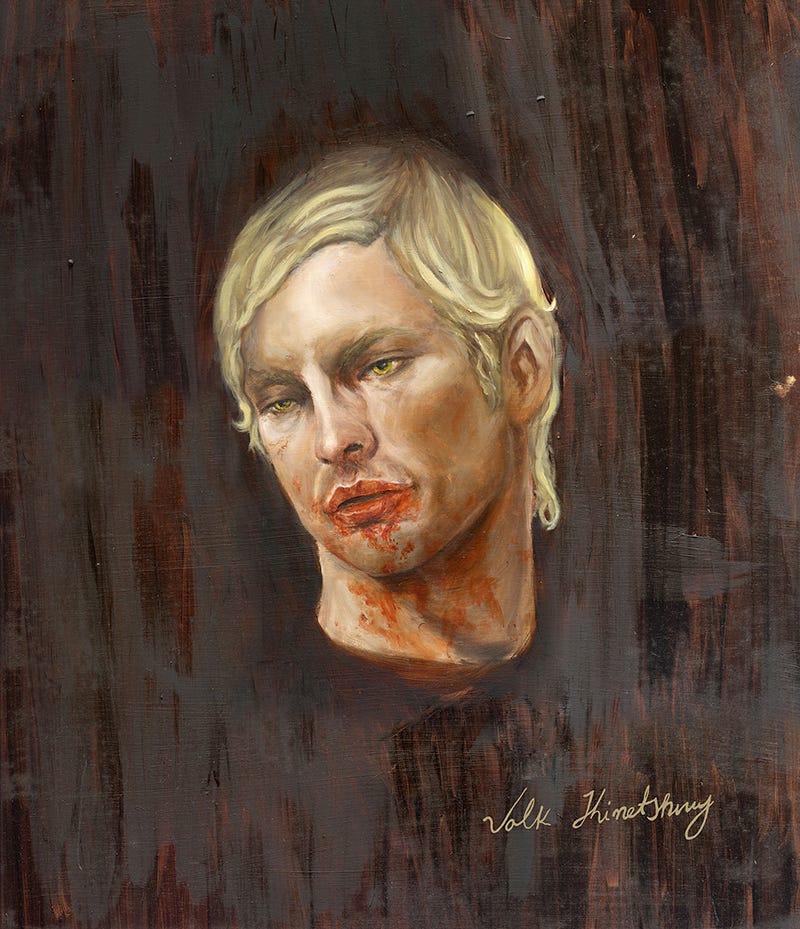

Dahmer’s victims are not really part of my art as people—merely as symbols related to Dahmer (for example, the skulls), which are there to identify and describe him, his actions, and his reality. Art needs to be subjective, and the Dahmer series is not about giving out information or judgment on what Dahmer did; it’s rather trying to depict the whole of Dahmer from within.

He might have done gruesome things, he might have felt helpless, he might have felt evil, demonic even, he even might have felt proud for all the things he did. All those things together—his possible break with reality, like wearing the yellow contact lenses to hunt—so that he could be more like the demon— that’s what my series is about. So in his world, the victims were just objects or symbols, and that’s what they remained in my paintings.

But do you ever consider your art's impact on the victim’s families?

A new level of outrage has appeared in the culture related to Dahmer after the Netflix series returned him—full-bloom—into everyone’s imagination.

Because you are both an artist and versed in criminal psychological studies, I’m curious to hear your impressions on this theme.

Well, this question has many aspects to it. I’m sure most victims’ friends and families have been traumatized, and I’m including friends because sometimes friends can be much closer than families, so I feel it will have the same impact on them as well.

I think people will be angry and will hate everyone who did them harm and everyone who doesn’t stand by them; that’s in their nature. They will not want the murderer to have the right to a lawyer, yet the system believes it is essential to provide one.

They will not believe that the murderer is allowed to gain forgiveness, yet the church believes that anyone can be forgiven.

The thing is that the world is not built around our personal likes and dislikes. We can build our close world however we want, but we can’t control things outside of it.

There has always been art that focuses on depictions of disasters and death which could retraumatize anyone who has lived it or who has lost someone because of it. Paintings and statues of wars that had countless victims and spread horror to so many people. And, of course, war heroes.

We need to take into account that war heroes in some countries are considered murderers by others (I’m not going to mention names because there are many, and I don’t want to make it personal for anyone). How will those people feel? Trauma is everywhere, but art should stay out of this approach if it wants to remain what it is.

Art is to challenge ideas, go where others are scared to go, explore deeper feelings and beliefs, and even depict something we fear. Art is not just flowers, angels, and beautiful, nice people, art is also unsettling, and this is why it has been filled with gore and pictures of mutilations, corpses, the devil, and so on.

Artists need to focus on their subject and what they want to reveal through their art; once they start thinking of the outcry and the response of those who will blame them for not considering them, it stops being art.

Aside from art and in connection with my studies, as a criminal psychologist, my job is to profile criminals and understand how criminals think and why they behave the way they do. For a criminal psychologist, the criminals are not their crimes, criminals are human beings who committed a crime or multiple crimes, but they are not monsters.

Far from it, we try to both predict their crimes or discover who they are by assisting police investigations, but we also care to see how we can treat them. Psychologists are not allowed to judge their patients, and out of all the psychologists, the criminal psychologist who is constantly working with prisoners and their psychological progress and rehabilitation need to know that judging someone is out of the question.

After announcing my novel on Substack and social media, a handful of individuals canceled their subscriptions or blocked my account on FB and IG.

I suspected that they never bothered to investigate my thesis—which is to work within an artistic discipline—to comprehend Dahmer in a unique, never-before-considered light. What has your experience been in this regard?

I’ve received a great deal of hate mail and attacks on social media. They’ve unfriended me or blocked me too, but it’s a good thing. I didn’t want people like that to be friends with me anyway. It’s narrow-minded individuals who are incapable of thinking and discussing, let alone tolerating another person’s opinion. So it was actually a good way to clear some space from people that aren’t worth your time.

Those are the kind of people that love to hate everyone and everything that is different. I feel those people identify you and me and anyone who is interested in examining things from a different perspective as “monsters” too. And the scary thing is they are not driven by some form of passion like serial killers are; they are driven by a rigid and sick moral compass.

I don’t have a religion, but I’ve studied them, and I believe it’s the same kind of people that were lynching the prostitutes that Jesus annihilated, telling them, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.”

And it’s those same people who were gathered to see the crucifixion of Jesus because they called him a fraud; they hated him more than anyone because they felt he was insulting their God, right?

I think there are a lot of interesting facts in religious texts if you read them with an open mind. And without equating anyone here to anyone, I’d like to quote Ted Bundy, whom I believe to be a very intelligent person. This was his quote regarding the cheering crowd at his execution.

“They are crazy. They think I’m crazy. Listen to all of them. Vengeance is what the death penalty really is. Really, it’s the desire of society to take an eye for an eye. And I guess there’s no cure for that. That’s society’s problem. Maybe we should find a cure for society’s problem.”

What are your impressions of the various social media accounts that feature Dahmer fan art—drawings, paintings, cartoons, and the like? Many of them are sexually charged or use meme-like humor in their composition. Do you see that content as simply serial killer obsessions playing out—or is something more finding expression?

How does the criminologist in you consider such creations?

I came across a few, and I think it all depends on who’s created the groups and the kind of people that join them. There are different kinds of people, I think; some are just obsessed with serial killers because they like creepy and dark things. Others seem to be more attached to serial killers on a psychological level, or they might identify different parts of them (not necessarily about the killing) because serial killers are just people who also happen to kill, so the fans might identify with other parts of their personalities or life.

And then there are those who feel sorry for them and wish they could have rescued them from being a serial killer. And, of course, there are a few who don’t really understand and treat them as if they were actors or any other celebrity, and they potentially fall in love with anyone who makes headlines (which, in my opinion, are the pointless ones in the groups).

So there are lots of different people in them. Leaving aside the last category, I believe it’s a phenomenon that should be studied more. We should ask those people for their reasons and let them explain how they feel. Mostly, from discussions with serial killer fans, I have had a positive experience, and they seemed like people who had gone through a lot or had considered things in a more open way.

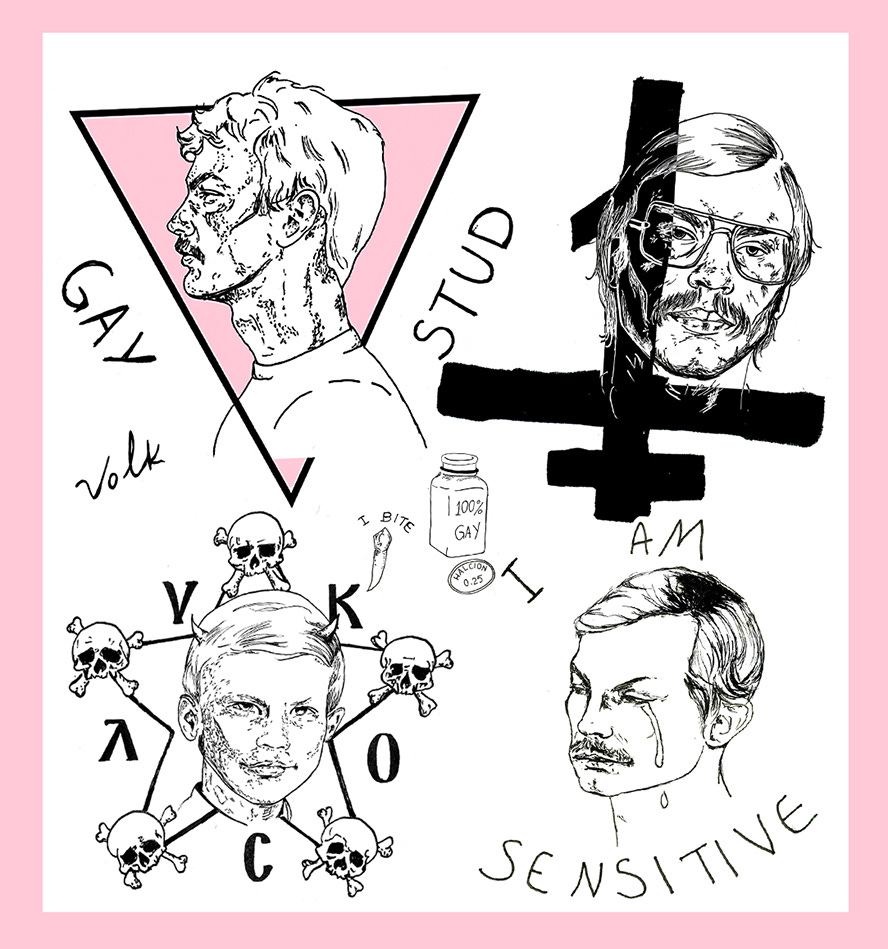

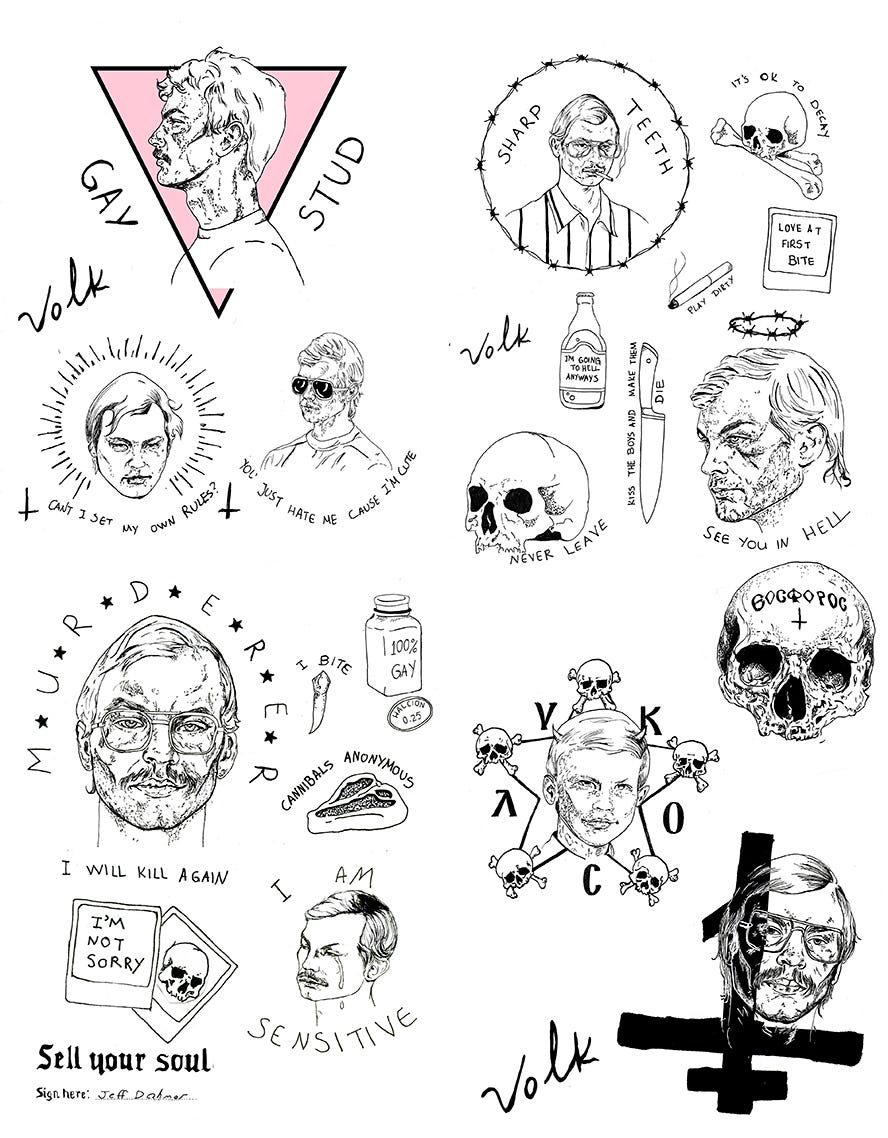

Your Dahmer Russian prison tattoos have a whimsical subversive vibe. I found myself conflicted—as I’d start laughing at the more outrageous ones.

How did these designs come about amidst your technically detailed and serious paintings? Do you feel they are a compliment to the more somber paintings?

Yes, the tattoos are supposed to be funny. The thing is, the tattoo ideas just came to me because I was thinking of tattoo designs for a tattoo event my sister and I was going to attend. I didn’t think of it as a complimentary aspect of the paintings, but then I thought they would go well with my Lucifer, my dear exhibition, so I incorporated them.

I like to combine the Russian prison tattoo style with pop culture, and both have a funny element to them and are over the top. And I think if you look at Jeffrey Dahmer from a different, more detached-from-reality perspective, it can be funny—so that’s what I used for the tattoo designs.

What is next for you with your Dahmer odyssey?

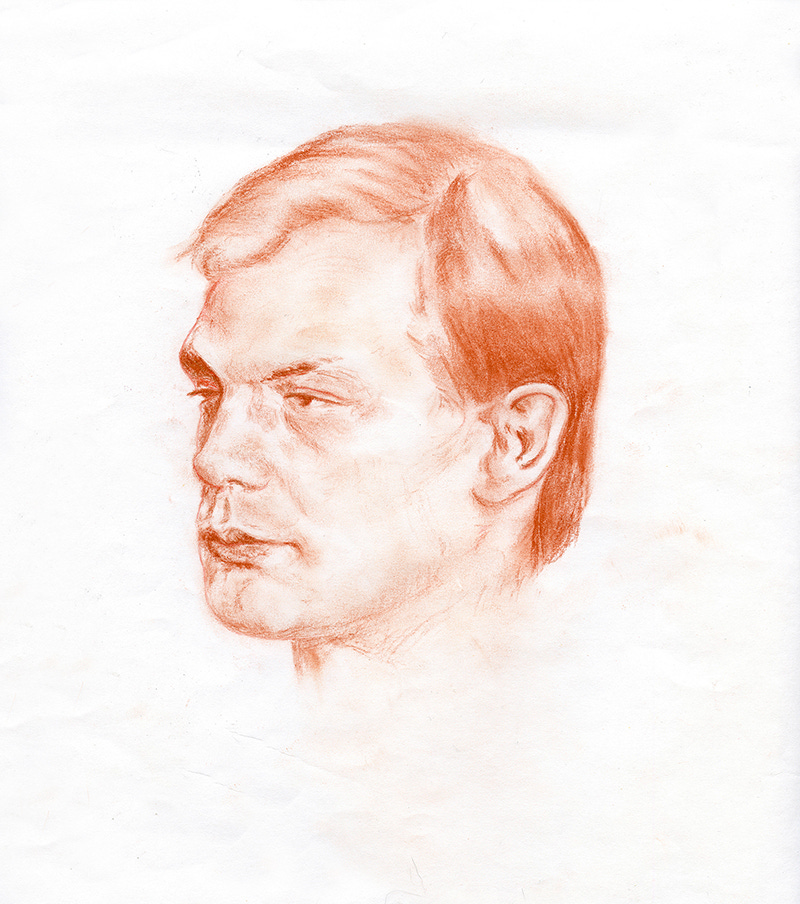

I’m not sure, I’m still thinking about it. My current painting project is called “Unseen,” and it’s about a form of underworld or neverland. I’m using various models for the paintings that I will include, and perhaps there will be one of Jeffrey Dahmer too.

Apart from that, I’m going to release my dissertation as a book, and Jeffrey Dahmer will be one of the five serial killers I will analyze. But I’m still revising and reshaping it, so I don’t really know when it’s going to be ready. It’s pretty stressful—though I enjoy it.

How would you summarize what you’ve learned or experienced by having your work influenced by Jeffrey Dahmer as a muse? And how will this wisdom influence your work as a criminologist?

It was an eye-opener. The moment I “clicked” with him, I felt a whole new set of attributes unfold in front of me. My painting abilities improved drastically without any training in between, and I knew where I wanted to go with my life and studies—the time I spent reading every detail and observing every move and blink of his helped me explore a serial killer in depth.

I feel that it has been great practice for my criminal profiling experience, and in a way, he helped me decide on my Ph.D. topic on serial killers as well. My interest is in serial killers’ thought patterns, feelings, and behaviors, and I’m going to work on research in this field because I feel there are no satisfying answers so far since the approaches seem somewhat stagnant. Yes, so to sum it up, as weird as it might sound, I could say he shaped my path greatly.

This artist’s statement is so true:

“Artists need to focus on their subject and what they want to reveal through their art; once they start thinking of the outcry and the response of those who will blame them for not considering them, it stops being art.”

Right, art dies when it panders.

I’m thinking of the Renaissance masters and their indifferent portraits of merchants and patrons. Never as passionate as when a vision seizes them and they work from the gut. Caravaggio's street boys, for instance. Or wild altarpieces with angels and devils, glory and transfiguration.